A 51-year-old man has been unexpectedly cured of HIV after undergoing a stem cell transplant to treat leukemia, marking the seventh confirmed case of HIV remission achieved through this method. This case is particularly significant because it demonstrates that HIV resistance in donor cells may not be necessary for a cure, challenging previous assumptions and broadening the potential avenues for HIV eradication.

Rethinking the Cure: Beyond CCR5 Resistance

For years, the scientific consensus held that successful HIV cures following stem cell transplants relied on donors carrying a specific genetic mutation (CCR5 deletion) that renders immune cells resistant to HIV infection. Five prior cases supported this theory, suggesting that eliminating the CCR5 receptor was critical. However, a sixth patient – the “Geneva patient” – showed HIV remission without this mutation, raising doubts about its absolute necessity.

The latest case confirms these doubts. The patient received stem cells with only one mutated copy of the CCR5 gene, alongside a standard copy. Despite this, he remained HIV-free for seven years and three months after discontinuing antiretroviral therapy (ART) — the standard medication to suppress the virus.

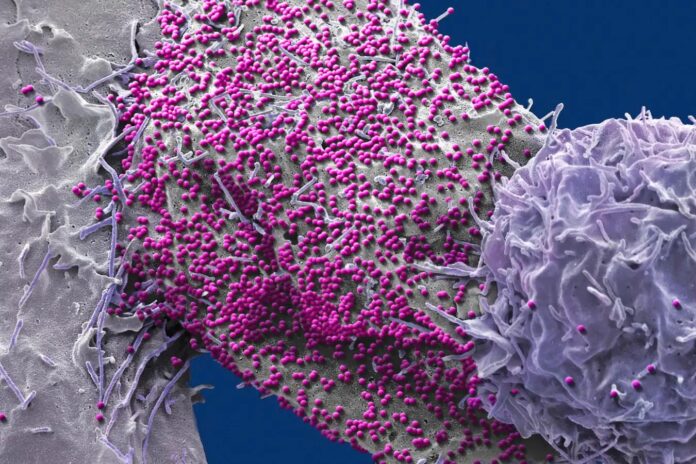

How It Works: Immune System Reset

The process involves chemotherapy to destroy the patient’s existing immune cells, creating space for the donor stem cells to rebuild a new, healthy immune system. Previously, it was thought that this new system had to be resistant to HIV. But this case suggests that the donor cells can eliminate any remaining infected cells before the virus can re-establish itself. The key may lie in immune reactions triggered by differences between donor and recipient cells, where the donor cells recognize and destroy the remaining infected cells.

What This Means: Broader Options, Not a Quick Fix

This discovery expands the pool of potential donors for HIV-curing transplants. It suggests that more transplants could lead to remission than previously believed. However, a cure is not guaranteed and relies on complex interactions between donor and recipient genetics.

It is critical to understand that stem cell transplants are highly risky, primarily used for treating cancer, not HIV. Most people with HIV are better off with safe and effective treatments like ART or newer long-acting drugs such as lenacapavir, which require only two injections per year.

Despite the risks, this research fuels ongoing efforts to cure HIV through genetic editing and vaccine development. This new understanding of immune responses in stem cell transplants provides valuable insights for these endeavors, moving us closer to a long-term solution for millions living with HIV.